©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Sanjit Das

Proponents of evidence-based policy increasingly highlight the importance of combining robust implementation research with impact evaluations to make decisions about the scale-up of international development programs. However, many recent studies indicate that successful pilot interventions fail to produce similar impacts when scaled up (Cull & McKenzie, 2020). Various challenges contribute to the reduced impact of these interventions, including – failure to account for diverse contexts, political economy and bureaucratic issues, difficulty in applying the same level of monitoring and oversight as for a small-scale pilot, and sometimes, general equilibrium effects.

Should we still expand these programs if impacts reduce after scaling up? To answer this question, we need to understand the relationship between scale and costs. Scaling decisions should be based on more than impact estimates, and while impact evaluations increasingly include costs and cost-effectiveness estimates, very little research examines the implications of scale for the cost-effectiveness of successful pilot interventions. As a result, policy implications of the studies examining the relationship between impact and scale remain unclear. The lack of cost considerations is puzzling because classical microeconomics clearly suggests potential cost-savings from economies of scale. What happens if economies of scale push costs low enough that they offset the lower impacts, and help retain the overall cost-effectiveness of the program?

In a recent working paper, we explored this question in the context of JEEViKA – the Bihar Rural Livelihoods Promotion Society (BRLPS). JEEViKA has been operating the Bihar Rural Livelihoods Project (BRLP) since 2007, and currently implements India’s National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM) through Bihar’s State Rural Livelihoods Mission (SRLM). Launched in 2011, NRLM operates in 28 states through SRLMs, which create and work with women’s self-help groups (SHGs) to facilitate institutional and capacity building, financial inclusion, livelihoods promotion, social inclusion, and development. When JEEViKA started in 2007 with funding from the World Bank and the Government of Bihar, it annually mobilized approximately 8,000 women into approximately 650 SHGs; today, the number has grown to more than 11 million women, or close to a 900,000 SHGs. The program starts with mobilizing women into SHGs and gradually introduces additional program activities like facilitating collective savings; access to formal bank accounts; forming higher-level federations [i], including village organizations and cluster-level federations; disbursing grants and loans to support livelihoods activities; and, in some cases, gradually introducing additional facets, including health and nutrition interventions.

We studied JEEViKA’s program expenditure data from annual audit reports between 2007-2008 and 2018-2019, and estimated costs of different program components, including capacity building, institutional development, and project management. We used these estimated costs to empirically test for economies-of-scale evidence. Further, we looked at how program costs changed with the addition of specific program activities, and offered some initial insight into how program cost-effectiveness may have changed with respect to scale. To answer the latter, we reviewed existing evidence on the impact of JEEViKA from a first evaluation that was conducted in its pilot phase in 2008 (Datta, 2015), and a second evaluation that was conducted after it scaled up in 2011 (Hoffman et al., 2021).

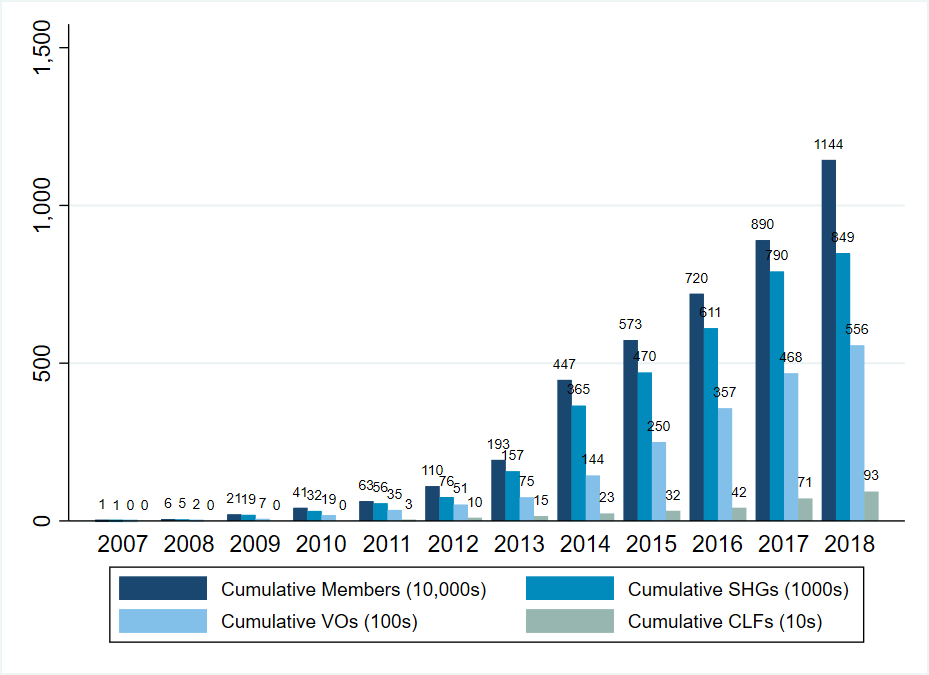

Figure 1. JEEViKA Program Scale-Up

Note: The x-axis depicts the start of a financial year, and ranges from 2007-08 to 2018-19.

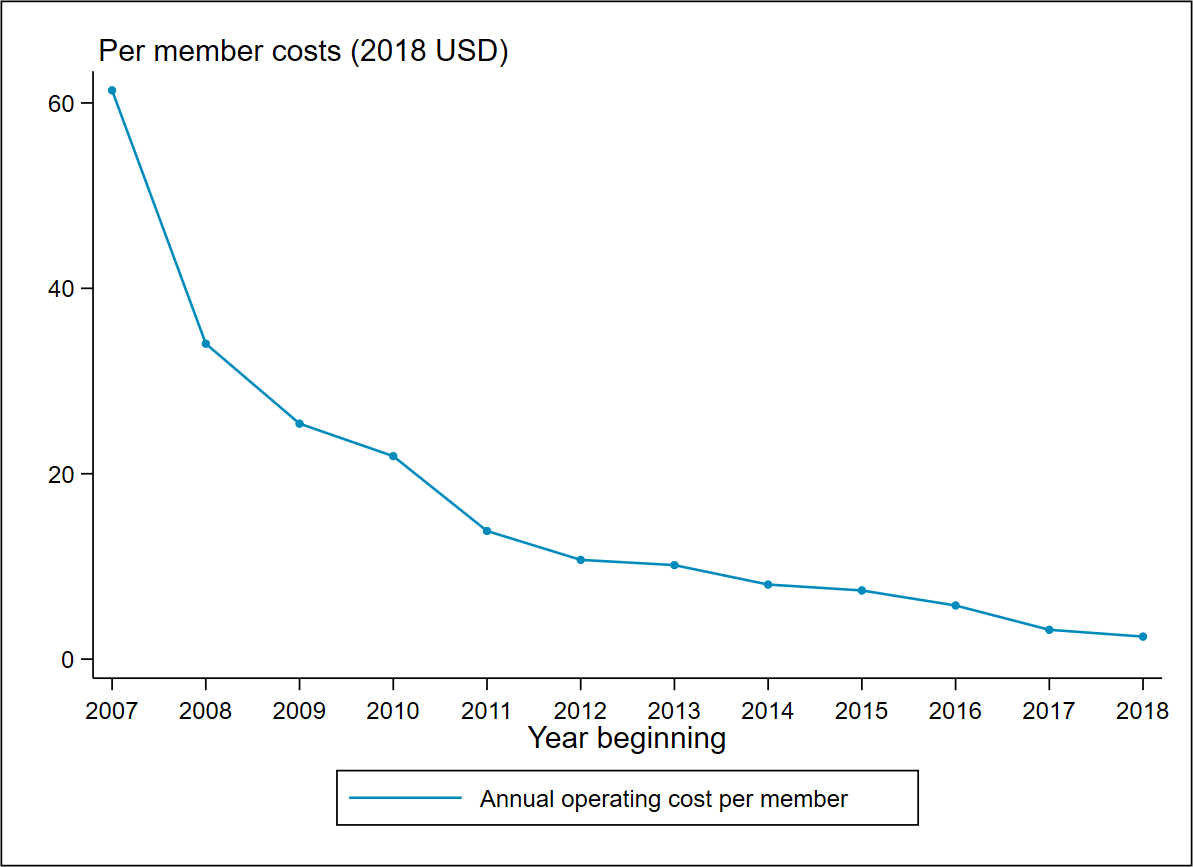

JEEViKA’s scale of operations expanded significantly between 2007 and 2018 (Figure 1). In 2011-12, JEEViKA took over the expansion of SHGs under the NRLM and received additional financing from the World Bank for the second phase of the BRLP. Figure 1 shows how the number of women joining SHGs increased steadily post expansion, especially after 2012-13, and by 2018-19 when over 11.4 million women had become part of almost half a million SHGs. At the same time, the per capita annual expenditure of the program declined consistently (Figure 2). We found that the average annual per-member expenditure dropped from almost $60 per member in 2007, when the program covered 8,000 people, to $6 per member in 2018, when the program covered 11 million members, assuming that all program members mobilized up to a given year continue receiving services irrespective of when they joined the program[ii].

The descriptive findings were supported by a formal regression analysis – our estimates suggested that annual expenditure per capita for the smallest level of outreach was $31. Increasing scale by an additional 100,000 members was associated with a decrease of 77 cents in per capita expenditure. The drop in costs per person seems to slow down when the program grows exponentially – suggesting that existing inputs may reach their threshold of productivity when scale increases by a significant number.

Figure 2. Annual Per-Member Expenditure

Note: The x-axis depicts the start of a financial year, and ranges from 2007-08 to 2018-19.

Our analysis also showed that total program costs changed with respect to specific activities within a program – formation of SHGs; bank-linkage of SHGs; forming of village organizations; and forming of cluster-level federations. A 1 percent increase in each of the four activities was associated with a less than 1 percent increase in annual program expenditure – indicating economies of scale across the board. Among the four activities, the number of cluster-level federations formed was associated with the smallest increases in costs, and SHG formation was associated with the largest increases in costs. Specifically, annual program expenditure increased by 0.49 percent with a 1 percent increase in the number of annual cluster-level federations formed, and by 0.77 percent with a 1 percent increase in the number of new SHGs formed. While forming an SHG is the first program activity following community mobilization, formation of cluster level federations occurs at a later stage, once groups have been functioning for a while, have formed village organizations, and have established the required capacity and infrastructure. This finding is especially important because a recent study of the NRLM found that SHGs worked considerably better after these higher-level federations had been formed. Specifically, Kochar et al. (2020) found that linking SHGs to higher level federations was associated with improved financial access and use of funds. Our cost findings suggest that these additional benefits can be achieved at a relatively low marginal cost.

Finally, we found that due to the economies of scale, the program maintained its cost-effectiveness in terms of costs per dollar of reduced high-cost debt. Specifically, we reviewed findings from two impact evaluations (Datta, 2015; Hoffman et al., 2021) – the first focusing on the initial pilot phase of JEEViKA (pre-2012) and the other on the second phase during scale-up (2012-2014). Findings from these studies suggested that while the project was able to generate strong positive effects, especially on social empowerment, in the pilot phase, the second phase (post-2012) failed to produce most of these individual-level and household-level effects. However, the strongest effects of JEEViKA were observed on reduced dependency on high-cost loans – in both pilot and scaled-up evaluations. Before 2012, that is in phase 1 of the project, the average high-cost loan amount decreased by $89 because of the JEEViKA program, more than twice the average impact of $33 in phase 2. Yet, combined with our findings on cost-efficiencies due to economies of scale, we found that it cost 91 cents to reduce each additional dollar of high-cost debt in phase 1 – only slightly different from 88 cents in phase 2.

Considering the relationship between program impact and scale in isolation from the relationship between program costs and scale, presents an incomplete picture when translating results to policy recommendations and action. Policy makers and funders must weigh scale implications for impact against the impact of scale on costs. However, cost-efficiency is not very meaningful if the program fails to achieve any benefits when scaled up. Program implementers must identify the elements that are critical to success early on, and monitor programming to ensure that they are implemented with fidelity even at a higher cost, while noting that overall average operational costs will still benefit from economies of scale. Implementation studies on JEEViKA suggested that gathering contextual information and adapting messaging for mobilization was critical for achieving positive effects on women’s empowerment in the initial phases of the programming but were difficult to implement in the second phase because of pressure to scale up quickly (Majumdar et al., 2017). Strengthening these program elements at scale could increase the cost-effectiveness of JEEViKA in other domains (besides financial inclusion) even with the associated higher costs, as long as JEEViKA maintains the elements that were critical for success during the pilot phase. In addition, emphasis on forming higher-level federations is an important factor for the collective economic upliftment of their SHGs and its members – and we show that JEEViKA could achieve these benefits at a relatively low marginal cost.

Finally, we note that although our study primarily focused on costs, we were able to integrate our results with existing findings and make recommendations because of a rich record of impact and implementation research of JEEViKA. We hope that future research on women’s groups continues to place emphasis on all three elements of a successful evaluation – impact, implementation, and costs – not in isolation from each other, but by putting the accent on tying these elements together at the outset of the study design.

Footnotes:

[i] The federated structure of SHGs under JEEViKA facilitates collective action, adoption of livelihoods enhancement and income generating activities, and development of linkages with market institutions

[ii] In our paper, we follow different assumptions for the size of member base that would be covered by the costs in a given year and find the same outcomes on economies of scale, irrespective of model assumptions.

Further reading and references: