©Gates Archive/Ricci Shryock

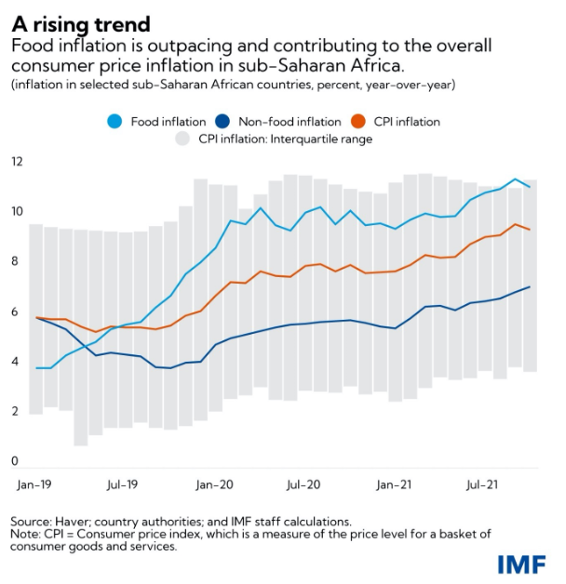

The crucial importance of savings groups to protect vulnerable and underserved groups in times of economic shock was evident throughout the pandemic: research showed a correlation between savings groups membership and food security at the household level. However, while individual resilience increased through membership of savings groups, the groups’ resilience suffered over the long term as they dipped into their pool of funds to help members cope. This threat is becoming far more apparent in the high-inflation environments that many savings groups operate in, especially as members experience spiking prices in food. Currently available interventions and solutions, including government programs and private-sector solutions, fail to adequately address the pressing issue. With the current economic downturn, the disintegration of some of these savings groups is not out of question.

Loans Accessibility For Survival

Access to outside credit continues to be critical for the survival of informal savings groups in a high-inflation environment — and subsequently for individual members to attain credit through them. While middle- to upper-income individuals have access to loans from multiple sources, including banks and microfinance institutions, lower-income members of savings groups have limited access to these providers. There have, however, been steps to help these groups gain access to credit. Governments have set up programs to help these groups grow, including Nigeria’s Agriculture Credit Guarantee Scheme Fund, Uganda’s Women Enterprise Program and Tanzania’s Mwananchi Empowerment Fund. Kenya’s Uwezo Fund offers group members, comprising women and youth, loans at low-interest rates from US$500 to US$5,000. However, implementation of these programs is often problematic. Nigeria’s agriculture loans are riddled with bureaucracy, making them hard to access quickly or at all. Samson Animashaun, a PhD research student at Olabisi Onabanjo University in Nigeria whose research involves interacting with farmers groups in rural Nigeria, has seen the inefficiencies firsthand.

“The loans are not going to those farmers directly. There are a lot of intermediaries. The loans are delayed…the farmer may not get the money [for] one month or more. It may be the head of the village that facilitates the process, asking for documents and other requirements, taking them to the banks — making the timeline longer.” Samson Animashaun, PhD Candidate, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Nigeria

And in Kenya, issues of nepotism and cronyism in loan disbursement further prevent some savings groups from accessing much-needed credit. On their own, low-interest loans are not enough for savings groups to successfully navigate high-inflation environments. Typically lacking is training regarding monitoring and evaluation on the part of the loan providers to ensure their good use and eventual repayment. Youth groups that received loans from Kenya’s government, for example, experienced poor performance, with few projects turning a profit or employing more than one person. Loan disbursement amounts are also often too little to properly support businesses. The consequence is chronically low repayment rates; Kenya’s Uwezo fund has only a 39% repayment rate, for example. Savings groups are left to utilize government-provided loans at their discretion, yet there’s little training done to ensure loans are utilized properly and repayments can be made.

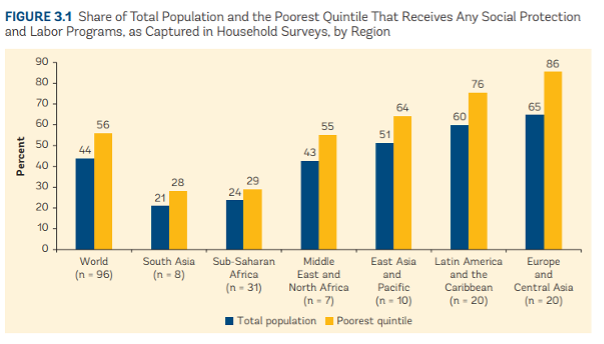

Further efforts towards ensuring access to daily needs are necessary, including provision of cash transfers and other social protection interventions. Individuals are often pushed to use loans for their daily needs such as food items, which complicates their ability to repay the loans. These programs, however, remain small, catering to an inadequate number of people. For reference, Sub-Saharan Africa sees only 29% of the poorest receiving any kind of social protection, compared to 86% of the more developed Europe and Central Asia in 2018.

Source: World Bank

In the private sector, microfinance institutions may find it in their best interest to increase efforts towards providing low-interest loans to savings groups. A focus on savings groups, which often have more female members, leads to better repayment rates. For instance, Nigeria’s Beyond Credit provides insured loans to micro enterprises to help scale their businesses. Building on the social capital approach, Beyond Credit enables savings groups to survive by grouping women into support groups of about six members to encourage saving and loan repayment. Beyond Credit boasts an impressive 99% loan repayment rate, according to the institution.

A Shifting Mindset

Where reliance on social protection is not possible, the most likely savings groups to survive are those that shift to an enterprising mindset. Groups that focus on building businesses and accumulating assets have been showing resilience in the midst of economic shocks. As part of the shifting mindset, members of savings groups often join more than one group, using each for a different purpose. One member of a self-help group in Dagoretti, Nairobi Kenya, tells Mondato Insight of the importance of being in more than one group.

“You have to be smart! I have four groups: one is to accumulate money to save in the other groups, one is to help me buy foodstuff in bulk, one helps me with business loans and one group invests in land so I will own some land one day.” Lucy Nanjala, Member of Tusonge Self Help Group, Dagoretti, Kenya

Nanjala’s strategic mindset enables her to cope with the rising inflation. It also gives some insight into the shift in mindset for group members who have started to realize that their savings can no longer just be put in a bank or a cash box and left alone. Savings groups that do more with their accumulated funds than simply giving them to one person during each contribution round are more likely to survive in the coming years, like those that invest their savings by loaning them out among themselves, start group businesses or invest in long-term assets such as land. While not all groups can make large investments, there have been numerous small businesses initiated by savings groups, including chicken or pig rearing, home-made soaps, car wash businesses and low-cost rentals.

However, despite the shift in mindset, there remains a lack of innovation in the space, with many groups simply copying what others have done, increasing supply to levels higher than available demand. The copycat behavior, while troublesome on a sector-wide scale, is the groups’ way of playing it safe in a high-stakes environment in which failure may mean going to sleep hungry or being unable to pay rent. To combat the replication of businesses, social safety nets (cash transfers, pensions) that cushion these members in the face of failed businesses are necessary, as well as trainings and workshops for group members to explore multiple business options for them to pursue.

With banks rather unattractive to savings groups, fintech alternatives to banks have emerged, offering some reprieve. These provide more tailored products, most often in the form of apps for the groups, as recently outlined by Mondato, with one aimed at helping people through the high inflation rates. Xend Finance, a Nigeria-based DeFi bank, enables individuals and savings groups to save their money in the form of cryptocurrency. Catering to people who don’t understand blockchain, the startup promises up to 15% interest rates on savings. However, with the recent crypto plunge and global inflation, the maintenance of such high interest rates for savings groups through cryptocurrency appears far-fetched.

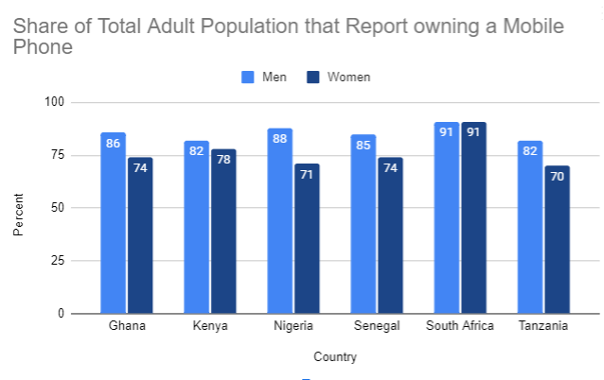

Beyond an uncertain crypto environment, app-based solutions only apply to a limited number of savings groups. Groups at the bottom of the pyramid may not have access to smartphones, leaving them out of such technology-driven solutions. While the Internet and mobile phone usage are on the rise across Sub-Saharan Africa, the increase is mostly concentrated among the younger populations and urban areas.

“Mobile phone ownership is still lower among women than men, especially in rural areas. Oftentimes when a household has one mobile phone, you would expect the man to have ownership primarily. And so the poorest members of savings groups would not benefit from fintech.” Thomas de Hoop, Principal Economist, American Institutes for Research

Population statistics in Uganda illustrate how in Northern Uganda, less than 25% of women own mobile phones, while in Nigeria, only 18% of women in the lowest income group owned mobile phones, compared to 57% of men. The trend persists on a country level across multiple countries. Considering the women-majority membership of most savings groups in Sub-Saharan Africa, the market base for digital financial services among savings groups is limited. Without bridging the gender gap, savings groups without access to such services may be left behind.

Source: PEW Research 2018

High Resilience Despite Increased Economic Shocks

Challenging economic conditions notwithstanding, those at the bottom of the pyramid have proven themselves to be surprisingly resilient. Research done during the pandemic showed women’s group members from Mali shifting from selling food at schools to selling masks to customers when schools were closed. And when it comes to money management, despite their limited funds, those at the BoP are able to manage their money well.

“The poor are often better able to manage finances than many non-poor people. If I make an expense, I don’t necessarily have to think about each and every expense that I make, [unlike] the poor, [who] have to make all these choices [with budget constraints].”

Thomas de Hoop, Principal Economist, American Institutes for Research

According to de Hoop, these people will find ways within their informal means to manage their finances and acquire more of what they need to survive. Subsequently, members of savings groups are likely to survive inflation — but at the cost of these savings groups, especially where the groups lack outside help in the form of credit, training and opportunities to grow their savings.

To help communities at the bottom of the pyramid in Sub-Saharan Africa, social safety nets, such as cash transfers, have been in place before and during the pandemic along with food distribution programs to help people cope. As Mondato Insight discussed last year, many cash programs digitized amidst pandemic pressures. This digital transformation did away with chaotic scenes of large crowds waiting for physical cash, making it easier on both parties. However, coverage of social protection programs like cash transfers among the lower-income communities remains low in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to more developed regions.

With inflation as high as 16% in Nigeria, the value of these cash transfers are rapidly diminishing in the current climate. De Hoop suggests an inflation-adjusted cash transfer program to protect the vulnerable groups. Such a suggestion may, however, prove difficult based on limited political goodwill. Ineffective implementation of cash transfer programs may also hinder key persons from accessing these much-needed funds, as Kenya experienced with its 2020 social protection program; lacking clear rules or transparency, the program was criticized for leaving out swathes of needy families, with numerous target communities never hearing of the program.

A Holistic Approach

There are some fintech products tailored to savings groups, though not many. Diamond Esusu, an app provided by Diamond Bank in Nigeria, allows people to start savings groups and conduct their transactions within the app, for example. Stanbic Bank in Uganda also has a Society Account for groups looking to put their savings in a bank.

But a closer look at these products reveals issues that limit who can access the products. Stanbic Bank’s requirements for savings groups to bank with them include a group constitution, minutes of the groups’ meetings and a permanent address, among other requirements that often wouldn’t be attainable for informal savings groups. And in practice, such bank products are typically limited to people within urban areas who can easily pop into the bank after their weekly or monthly meetings to deposit their contributions or conduct other transactions. Such hurdles are in addition to the low-interest rates that banks tend to offer — not exactly enticing in a high-inflation environment, in which members find that they’re better off ensuring their savings are utilized each meeting period through loans among members.

The most effective solutions may be less sophisticated but focused on enabling the holistic, social capital-oriented benefits of savings groups. Nigeria’s Beyond Credit offers a more human-centered approach by organizing women in small support groups to encourage saving and loan repayment, offering financial training as well. When compared to other microfinance institutions offering small loans at high interest rates — and potentially diminishing available safety nets among the poor — Beyond Credit encourages a build-up of individuals’ savings and promotes financial literacy as well as business development.

Beyond Credit offers a roadmap that not all savings groups can or will take. Select savings groups will survive if the high inflation environment persists, but their survival will be dependent on their access to means that enable them to dynamically grow their funds beyond the personal contributions of their members alongside inflationary pressures.

This blog was first published on Mondato's website. Mondato is a boutique management consulting firm specializing in strategic, commercial and operational support for the Digital Finance & Commerce (DFC) industry.