©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Liz Gilbert

Adolescent girls face numerous risks during their transition into adulthood, from early marriage and pregnancy to gender-based violence and dropping out of school. Failing to support girls during this transition period can lead to lifelong impacts on their labor force participation, reproductive health, and economic outcomes. In February 2020, the Evidence Consortium on Women’s Groups shared results of their portfolio evaluation of 46 investments in women’s groups made by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, some of which focused on adolescent girls and young women (ages 10-24). Given the importance of adolescent girls and their specific needs, I expanded on the evaluation by conducting a qualitative analysis on 17 of these investments that broadly included adolescents, exploring the pathways to impact for girls’ groups. Through reviewing documentation and evaluations, I examined program characteristics and how groups use interconnected pathways to achieve concurrent outcomes. I also reviewed the extent to which groups are linked to institutions and their communities. Here, I lay out some reflections and takeaways from my review. In general, investments:

- included inputs and characteristics of group elements that are hypothesized to improve women’s economic empowerment

- pursued multiple pathways available through groups to achieve target outcomes

- targeted girls’ community gatekeepers with multilevel activities in tandem with group-based interventions

Investments targeted multiple thematic areas and groups often encompassed broad age ranges

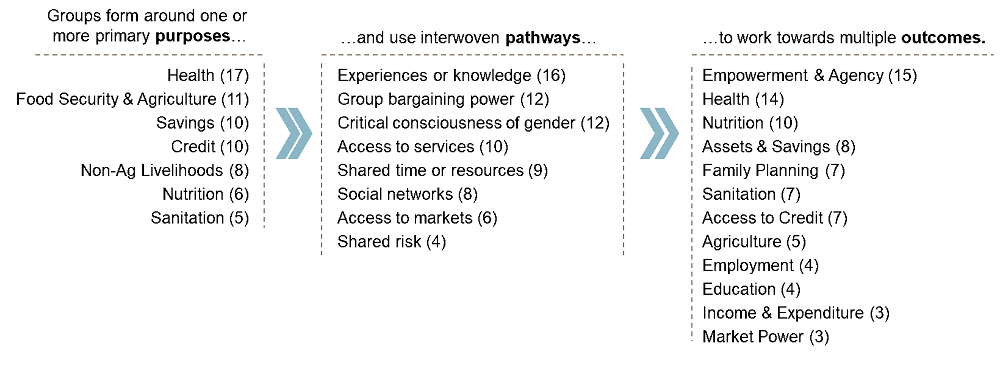

The 17 investments in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia were most frequently led by the family planning, nutrition, and maternal and newborn child health strategy teams at the foundation. Group purposes, intended pathways, and target outcomes are outlined below.

Figure 1: Group purposes, pathways, and outcomes

Some groups focused specifically on adolescents, while others included adolescent participants through broad participant criteria such as “women of reproductive age”. When adolescent girls and young women were specifically targeted, the age ranges were often wide, and criteria varied considerably such as “girls aged 10-19” or “young women” (with notable exception detailed below). All adolescent-specific programming used girl-only or gender-segregated groups. However, groups with both adolescents and adults sometimes had mixed gender compositions, particularly when programs leveraged pre-existing livelihoods groups.

Adolescent groups incorporated many elements typically used by women’s groups to achieve empowerment

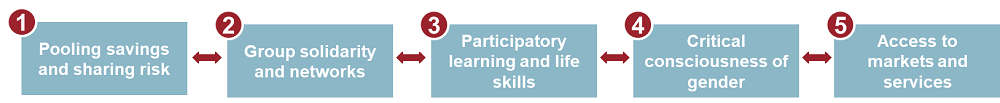

The foundation’s Gender Equality strategy seeks to build Women’s Empowerment Collectives (WECs)—a subset of women’s groups that target women’s human, financial, and social capital. The Gender Equality team has hypothesized that inclusion of the five group elements below can lead to women’s economic empowerment:

Figure 2: Group Elements

I examined the extent to which grantees reported the presence of these elements in adolescent and young women groups. Documented program designs typically included inputs or characteristics of three or four of elements. “Participatory learning and life skills” was most prevalent, in which group members could engage in relevant trainings on topics such as gender equality, health, life skills, and sanitation. Partners employed a variety of techniques to share information, including didactic learning, peer education and group discussions, as well as building community capacities.

While none of the adolescent-specific groups included all five elements, the Abdiboru project in Ethiopia provides an illustrative example of what four WECs elements can look like in a girls’ group. This action-research project led by CARE, in partnership with Addis Continental Institute of Public Health (ACIPH), aimed to empower adolescent girls ages 10-14 by improving their sexual and reproductive health as well as their education, nutrition and wellbeing through girls’ groups, implemented in tandem with community and government-level interventions. The group model had inputs or characteristics of four elements:

- Pooling Savings & Sharing Risk – VSLAs can financially benefit girls and serve as the entry point for layering additional support

- Group Solidarity Networks – group members have a safe space to share their problems and challenges with other girls

- Participatory Learning and Life Skills – training in life skills, gender equality, and sexual and reproductive health through a peer education model

- Critical Consciousness of Gender – girls’ groups include gender equality training and topics that target their decision-making and leadership skills

Programs use multiple pathways within a group to pursue target outcomes

In their brief, the ECWG identified the following pathways that are likely available to women only through a group:

- Shared or pooled risk, time, financial and/or other resources

- New or shared social networks, group commitment devices and mutual accountability

- New or shared experiences or knowledge

- Critical consciousness around gender, agency, and norms

- New or additional access to markets, services, or political/social bargaining power through numbers and collective action

As reflected in recent evidence reviews (1)(2), some pathways emphasize leveraging the group as a delivery platform to provide women with knowledge or resources, while others intend to foster peer interactions within the group to build social networks or bargaining power. The programs I reviewed often aimed to achieve their objectives through both of these mechanisms. For example, Jhpiego’s group antenatal care (ANC) program engaged cohorts of pregnant women ages 15+ in Nigeria and Kenya with facilitated group discussions and individualized health assessments. Participants also shared their challenges and formed relationships with other women at similar gestational stages. In both countries, women participating in the group model attended more ANC contacts than those receiving individual care and received better quality care. The evaluators hypothesized that peer groups can generate a self-reinforcing cycle that motivates women to continue care, supporting the idea that groups have the potential to deliver benefits through interactions among members.

Across outcome types (health, empowerment, financial inclusion, livelihoods), programs targeted multiple, interconnected pathways and evidence isolating the effectiveness of a single pathway is limited. Creating experiences and knowledge was a commonly planned intermediate pathway to distal health, livelihood, or empowerment outcomes. However, this pathway alone may not lead to target outcomes for group participants. In assessing the impact of a video-enabled agricultural extension program in Ethiopia, Abate et al. found that, while including women (spouses) in group learning sessions did increase their access to extension services, they did not find evidence that the program ultimately improved adoption or yields. Other programs were designed to build additional pathways in tandem with experiences and knowledge. Group discussions and peer interactions used in trainings were intended to foster group bargaining power, which may create linkages to services for group members. A sanitation program led by the Centre for Advocacy and Research (CFAR) provides an illustrative example of this interconnectedness. Multipronged activities were implemented through women’s groups in at-risk urban communities in India. Adolescent group programming included training on menstrual hygiene, using peer interactions such as group exercises, role plays, and discussions where girls could share their concerns about menstrual hygiene. Girls were also connected to Gender Resource Centers, which provided them low cost sanitary napkins. The multiple pathways of knowledge and experience, group bargaining power, and links to services worked in tandem in pursuit of improving girl participants’ menstrual health. The program observed that girl participants’ attitudes and knowledge of menstrual hygiene improved, as did their use of sanitary products.

Investments in groups also included activities to engage girls’ enabling environments

Investments included multilevel programming targeting girls’ enabling environments in tandem with group-based interventions. Most investments (14 of 17) collaborated with or supported a government agency, at either the local, state, or national level. Some aimed to shift norms within communities and households by engaging gatekeepers such as parents, family, or community elders. Recent research on the effectiveness of multilevel programming, indicates a general lack of evidence, but promising emerging results. A systemic review of adolescent programs in low and middle-income countries found that evidence on the effectiveness of multilevel programming was inconclusive. In their comprehensive review of community-based girl groups, Temin and Heck note that the effects of community engagement activities on girls’ outcomes are rarely included in impact evaluations. The Population Council shared emerging findings in “Delivering Impact for Adolescent Girls” that empowerment and asset-building interventions for girls that also included activities directed at community members can improve girls’ economic, health, education and empowerment outcomes. While evidence gaps remain on cost-effectiveness, relative impacts, and implementation science, learnings from the field point to the potential for multilevel programming to improve outcomes for girls.

Partnerships with governments involved identifying and evaluating models that work for girls, building agencies’ organizational capacity and technical knowledge, or linking groups to services and additional layers. For example, Pact’s State Accountability for Quality Improvement Project (SAQIP) in Nigeria’s Gombe State formed mother’s groups (targeting women of childbearing age, 14+) in tandem with multilevel interventions:

- Government: Build capacity at the State Primary Health Care Development Agency (SPHCDA) through staff co-location and coaching, inter-agency coordination and transparency, and improving data generation and use

- Community: Improve community monitoring of the public health system by strengthening Ward development committees through community scorecards and capacity development

- Women’s groups: Increase women’s use of maternal health services through group savings, literacy training and MNCH education

However, partnering with governments is not without challenges. Political instability, leadership turnover, and shifting priorities created delays, disruptions, or revisions to program activities for some investments. For example, CFAR’s urban sanitation project (referenced above) began with a formal technical partnership with Delhi’s Mission Convergence program. However, the launch of a new national sanitation program and shifting agency roles necessitated major changes to the project’s strategic partnerships, which pivoted to urban development entities.

Other projects targeted determinants of girls’ outcomes at the community-level. In tandem with girls’ groups and government-level activities, CARE’s Abdiboru project (referenced above) implemented recurring community dialogues through their Social Analysis and Action framework. Adults regularly met to discuss gender norms, including household task sharing and early marriage. By having adults go through a similar process of norm-challenging as the girls, the SAA program aimed to create space for girls’ agency to play out and reinforce what they learn. The project’s forthcoming evaluation, conducted by ACIPH, was designed to assess the marginal impact of SAA programming on girls’ outcomes by comparing the three-level intervention (girls, community, government) to a two-level model (girls, government) and a control group (without interventions). Further studies designed to identify the impacts of multilevel interventions on girls’ outcomes are needed to bridge evidence gaps.

Protecting the interwoven benefits of groups in our current crisis

Overall, group pathways and multilevel relationships are interconnected and their marginal impacts are difficult to disentangle. Across outcome types, groups use multiple pathways in pursuit of their goal—some that may build on or reinforce each other. While evidence gaps remain, learnings from the field point to the potential for girls to benefit from groups as a delivery platform for knowledge and resources, as well as through the social networks they build through peer interactions. Interventions working at multiple levels of girls’ environments show promise and I echo the interest shared by the above authors in seeing further study of their efficacy on girl-level outcomes.

Today, these benefits are threatened by the COVID-19 crisis, as lockdowns prevent some girls from participating in group-based trainings and social distancing limits their peer interactions. However, limited past experience has indicated that peer groups have the potential to provide girls with critical support during a time of crisis. During the 2014 Ebola outbreak, Bandiera et al. found that adolescents who were part of girls’ clubs in Sierra Leone were less likely to become pregnant or drop out of school compared to those who were not. In our current crisis, it will be important to see how groups can adapt and how funders, governments, and implementers can respond and support girls during this time of need.