©AMMACHI Labs

Financial and accounting training can help self-help group (SHG) leaders address managerial gaps that constrain SHGs’ economic development. These gaps may include lack of leadership and traceability of financial transactions, for example. The preliminary results of a training with 30 SHGs in 3 Indian villages suggest enhanced confidence of SHG members to hold effective meetings, increased SHGs’ financial maturity, and improved saving attitudes, which are crucial elements to building SHG resilience in a sustainable manner.

Women’s economic groups are increasingly recognized as spaces to improve empowerment in low-and-middle income countries (Brody et al., 2016; Kochar et al., 2021, Kumar et al., 2021, Deshpande & Khanna, 2021, Nichols, 2021, Barooah et al., 2020), but the full impact of these groups on women remains uncertain. The large-scale National Rural Livelihoods Mission program implemented by the Government of India has led to the formation of above 7 million Self-Help Groups (SHG) meant to support women’s economic growth through easy and affordable access to saving and lending mechanisms. Financial inclusion is instrumental for women’s business initiatives, one of the program’s goals. However, investing in accounting and financial literacy is needed to enhance women’s use of such financial products and increase the NRLM’s effectiveness.

Though SHGs can often secure the financial resources to make investments and venture into business, many women still lack the knowledge, skills, and attitude to use their newly-acquired resources effectively. Indeed, the lack of literacy, specifically financial and accounting skills, and reduced exposure to entrepreneurial activities could prevent SHGs’ economic performance. A recent NRLM impact evaluation by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) highlighted the potential for SHGs to enhance their access to NRLM funds and audits and increase business initiatives through collective enterprises. For instance, only 1.5% of SHG respondents reported involvement in group entrepreneurial activities, whereas a branch of the NRLM is dedicated to providing vocational training for business development.

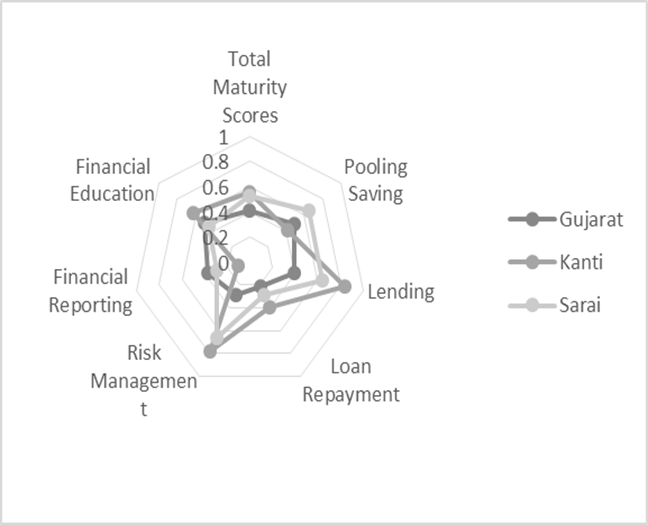

We conducted a need assessment in three locations in different Indian states (Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, and Gujarat), where we discovered some gaps SHGs face in tracking transactions, managing defaulters, and assessing lending risks (See Figure 1). This assessment indicated a lack of financial information at the group level. None of the groups involved in the study were aware of the due amount from their borrowers, despite the delinquency ratio1 being a critical indicator of lending activities. Improving financial literacy for women’s SHGs is necessary to successfully conduct their micro-lending activities and have the capital and know-how to engage in more expansive entrepreneurial ventures. SHGs’ contribution to women’s socio-economic empowerment seems limited without additional financial performance.

Figure 1: SHG financial maturity per location (Source: Authors)

A course tailored to SHGs’ needs

The Center for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality developed the SMART (Sustainable Management to Achieve Social Responsibility using Technology and Training) SHG course for leaders to support financial and accounting empowerment towards effective and profitable SHG management. The course aims to (i) Enhance bookkeeping & transparency, (ii) Identify and manage loan defaulters & lending risks, (iii) Strengthen leadership & democratic participation, and (iv) Improve interaction with stakeholders.

Several stakeholders directly participated in the development of this 65-hour course. Financial and accounting experts, a specialized instructional and digitization team, researchers, future beneficiaries, and grassroots stakeholders such as government representatives, banks, and NGOs were involved. First, the researchers collaborated with grassroots stakeholders in creating a conceptual model with structured competencies. Meanwhile, the subject matter expert interacted with SHG leaders and audited SHGs’ books to understand women’s needs and build specific training content.

Afterwards, the instructional and digitization team designed multimedia scripts and storyboards to produce rich interactive content and digitized activities for the engagement of low literacy users. Digital interaction may be a key factor of success because it helps provide training quality standards, raise the learners’ interest, and enable scalability.

In addition to the technical training, we added soft skills content with role-plays, debates, and real-life situations to engage women in discussion and problem-thinking scenarios and promote activity-based learning. Such activities help draw women’s attention and increase their motivation to participate actively in training by answering questions from trainers, clearing doubts, and interacting with other trainees.

Enhancing the Peer-Mentor Model through Digitized Training Content

The project followed three deployment phases: training master trainers, training SHG leaders as mentors, and mentoring SHG members. First, master trainers were trained by subject matter experts. Then, the master trainers taught the SHG leaders, who have the role of training their respective group members. Upon completing the leaders’ training, the master trainers evaluated SHG leaders, provided grade certificates, and conducted mock sessions with SHGs. Once the mock sessions were over, the leaders started SHG member training, the last deployment stage.

Though training effectiveness is often diluted when using a Train-The-Trainer model, our experience indicated that the availability of digitized content minimizes this risk. Indeed, the digital content helps ensure that all trainees have access to similar content and quality. In addition, the use of digitized conversations and real situations seems to be a more effective pedagogy for low-literate women learners who have difficulty grasping conceptual knowledge.

The digitized content was used in sequential steps: (1) watching the full video, (2) watching the video with breaks to discuss the content, (3) reviewing main concepts, and (4) concluding with key takeaways and small quizzes. Most of the sessions also included digital activities to practice the newly-gained knowledge. While testing the content, women showed enthusiasm to adopt this innovation and learn from it. However, they also faced a few difficulties navigating the content. So, we added a couple of pre-training modules to help women feel more comfortable using the tablet and user interface. All participants got the opportunity to interact with tablets while learning, and we received encouraging feedback from women on their experiences with tablets.

“The training was tablet-based. I’ve never seen one and did not even use any tablets before this training. When we started attending the training, we also learned to use it, and it helped me understand the contents and bookkeeping practices quickly.” Sangeeta, Shakti Ajivika SHG, UP

Encouraging preliminary impact results

We are currently working on two specific studies to assess the training impact in addition to the traditional certification examination. SHG leaders completed quizzes and practical exercises in groups as part of the certification evaluation on their technical skills. More than 30% of the trainees graduated with an A grade and another 30% with a B grade.

To estimate the program effectiveness at the group level, we run a comparative study on the SHGs’ financial and accounting performance before and after the training. Our innovative course specifically provides concrete accounting tools and templates for groups to track their lending practices transparently and ensure a timely repayment. We hypothesize improved accounting practices as immediate outputs, with a possible enhanced financial performance in the short-and-medium term.

To assess the program effectiveness at the individual level, we conduct feedback interviews with trainees to identify meaningful consequences of the training by applying the most significant change method. This evaluation work is instrumental in revising the Theory of Change and preparing for future deployment and evaluation work.

Preliminary analyses indicate that the training helped boost women’s saving motivation by providing knowledge and tools. Women appreciated how saving could be used to achieve a higher goal. For instance, one woman testified that “with savings, we educate our children well so that our children grow up and move forward and become somebody, do something, this is a big change.”

In addition, the training seems to clarify SHGs’ cash transactions considerably and prevent adverse outcomes. For example, one woman said that “they used to write information all together in the books, now they know where the loan is written, where the savings, where the interest is written.” Another woman reported: “We know how much principal and interest everybody has to pay each month with the accounting templates we learned. This is really helpful; no more confusion and conflicts.”

Gained knowledge of SHG managerial practices makes women confident to drive their SHG forward. For example, one woman explained that: “thanks to the training, we got a lot of information, how to talk and to whom, how to read in our meeting, what to say in the meeting, we have come to know a lot about all this.”

This pilot project was funded by Creative Synergies Consulting Private Limited under their CSR initiative.

- 1The delinquency ratio is calculated by dividing the number of loan repayments that are late by the total number of outstanding loans.